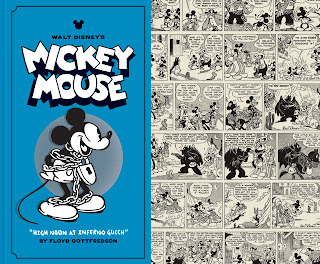

With Volume 3, the GOTTFREDSON LIBRARY well and truly swings into the "Golden Age" of the MICKEY MOUSE strip (button-eyed version). These strips from 1934-1936 show "creator-in-chief" Floyd Gottfredson taking full control of his stories and testing his range with tightly plotted domestic dramas and semi-dramas ("Bobo the Elephant," "Pluto the Racer," "Editor-in-Grief"), swashbuckling ocean-going adventures ("The Captive Castaways," "The Pirate Submarine"), Western sagas ("The Bat Bandit of Inferno Gulch," "Race for Riches"), and even a tentative stab at an extensive sojourn into another cultural milieu (the trip to Umbrellastan in "The Sacred Jewel"). There's literally something here for everyone, and one's favorite story will simply be a matter of taste and personal experience. For me, "Race for Riches" takes the palm, being the first Gottfredson story that I ever read, thanks to the late Bill Blackbeard's invaluable SMITHSONIAN COLLECTION OF NEWSPAPER COMICS. That early-1980s exposure predated my "deep dive" into Disney comics collecting by a couple of years, and I recall being both surprised and amazed at how much this mysterious man Gottfredson had been able to wring out of a character then universally regarded (by the vast majority of Americans, at least) as a bland corporate symbol. In retrospect, the fairly straightforward "Race," which sees Mickey and Horace Horsecollar (sharing their last "classic" adventure together) trying to beat the inevitable Pegleg Pete and the grasping Eli Squinch to a cache of hidden gold and prevent foreclosure on Clarabelle Cow's home in the process, was an ideal introduction to the world of the "death-defying, tough, steel-gutted Mouse" celebrated in Blackbeard's pioneering essay "Mickey Mouse and the Phantom Artist" (which is reprinted herein). It shows Mickey as a character capable of adventure, yet, in a sense, locked into what was even then considered a pretty conventional, melodramatic plot line. The "cognitive dissonance" between what I thought The Mouse was in the early 80s and what Gottfredson had conceived him to be half-a-century before would have been far more severe had I commenced my Gottfredson studies with the crusading Mickey who battled racketeers and corrupt politicos in "Editor-in-Grief" or the Mickey who took down the would-be world conqueror Dr. Vulter in "The Pirate Submarine."

In their commentaries and essays on the stories, Tom Andrae, David Gerstein, Leonardo Gori, and Francesco Stajano make the point that the Mickey seen here is a rather more mature character than the happy-go-lucky "kid" of the earlier strip adventures. This maturation process allowed for a somewhat more sober tone to creep into the stories. Reading the adventures in chronological order, I was also struck by the tone of cynicism (or, if you're being kind, realism) that Gottfredson brought to these tales. Isn't Carl Barks supposed to be the "master satirist" of Disney comics, the one who looked with a jaundiced eye on the faults and foibles of a fallen world? Here, though, Gottfredson presents us with a lengthy parade of crooked landlords, phony "community pillars," racketeers, petty race-fixers, insensitive kibitzers, pompous officials, wannabe dictators, apathetic (until roused) Mousetonians, bumbling sheriffs, knuckle-headed Middle Easterners... It's just a short walk from here to the approach taken by Gottfredson in his most misanthropic masterpiece, "The Miracle Master." I suppose that I can understand why Gottfredson did this -- to permit the occasionally-fallible-but-usually-competent Mickey to shine by contrast, and, needless to say, to make it easier to get laughs from the newspaper readership, with its expectation of a proliferation of gags to spice up the adventure narrative. But, geez, Gottfredson certainly doesn't need to apologize (or would that be the right word?) to Barks or anyone else when it comes to painting a begrimed background upon which to display his hero. The good cheer and simple competence of Mickey's Air Mail/Air Force ally Captain Doberman stand as a shining beacon by contrast. Perhaps in gratitude, Gottfredson slicks Doberman up considerably during this period, shaving a goodly number of pounds from the captain's frame, giving him a thorough shave, and even bobbing his ears between the time of "The Captive Castaways" and that of "The Pirate Submarine."

The presentation of "The Sacred Jewel" -- one of the few "classic" Gottfredson stories that Gladstone Comics did not reprint during the period 1986-1990 -- brings to mind another interesting point about Gottfredson's tactics during the "classic" era, one that, in this case, places him in direct opposition to Barks. "Jewel" marked one of the few times that Gottfredson took his characters to another civilized country, as opposed to a desert island, the high seas, the jungle, a prehistoric land ("The Land of Long Ago"), and other climes where civilization cannot be said to have wholly taken root. Therefore, this story has something of the air of a tentative, "feeling-one's-way" exercise, and its inconsistent nature reflects this. In the later, and much superior, "Monarch of Medioka," Gottfredson notably does not feel the need to inject Pete, Sylvester Shyster, Squinch, or any other familiar figures into the proceedings as visiting villains; the scenario and the setting of that story are strong enough to support themselves. He doesn't seem to have had nearly the same level of confidence in the denizens of Umbrellastan in "Jewel." As Gerstein notes, the characterization of the Umbrellastanians is all over the map, borrowing various French, Elizabethan English, and (of course) Middle Eastern tropes right and left. This tale provided an opportunity for Gottfredson to create a completely original adversary that reflected the local environment, but "the evil Prince Kashdown" gets virtually no screen time, with Pete and Shyster (who speak phony "Umbrellastanese" even when no one else can possibly hear them!) taking up the camel's share of the water, er, beer, er, oxygen. Barks, by contrast, dove right into exotic settings in "The Mummy's Ring" and never looked back; his depiction of such settings became more sophisticated over time, but the larger point is that Barks seemed drawn to creating and exploring unusual civilizations in a way that Gottfredson truthfully was not.

In the back of the book, following the "usual" features on characters, overseas reprints, and the like, Gerstein and Alberto Becattini present "The Heirs of Gottfredson: The 1930s School," focusing on Britain's Wilfred Haughton and Italy's Federico Pedrocchi. Pedrocchi gets especially cushy treatment with the reprinting in its entirety of "Donald Duck and the Secret of Mars," the creator's first serial for the fledgling Italian Disney publication PAPERINO. Donald may have been the star of this story, but it bears the mark of Gottfredson throughout -- an accurate reflection of just how immense of an impact Floyd had on the world market for Disney comics.

No comments:

Post a Comment