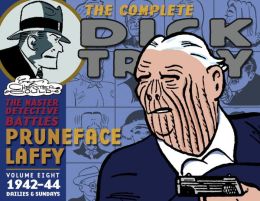

Garyn Roberts, in DICK TRACY AND AMERICAN CULTURE, identifies 1943 as Chester Gould's peak year on DICK TRACY. This may be a bit premature -- aside from the fact that plenty of memorable villains were still under the horizon, Gould had yet to create the rest of his stable of supporting protagonists (the Plentys, Sam Catchem, etc.) -- but it was at this point that Gould thoroughly committed himself to the "cult" of the grotesque villain. This latest collection opens with the introduction of the ruthless Axis agent Pruneface and closes with the opening salvo in the saga of Flattop, the planar-pated hired gun who's come to be more closely identified with Tracy than any other villain. Within these pages, we're also treated (if that's the word) to the most fiendish deathtrap Gould ever concocted for his put-upon plainclothesman, as well as one of the most obnoxious bad guys Gould ever created. Oddly enough, though, the very best complete continuity in the volume, at least in my opinion, owes a lot more to the sensibilities of the 1930s than those of the 1940s.

As threatening and vicious a villain as Pruneface is, he's basically a dry run (dry? prunes? that's a joke, son) for the very similar, and somewhat more fully characterized, Brow of the following year. Pruneface's sabotage, if successful, would have led to the killing of many civilians, but his persona lacks the clever, humanizing touch that was given to The Brow when the latter fell for Gravel Gertie. What makes the Pruneface tale memorable is that it's bookended by Tracy's near-fatal encounter with the hideous Mrs. Pruneface, who craves revenge for her husband's death (actually, she was operating under a false assumption, as PF would make a comeback many years later) and seeks to enforce it using the aforementioned death trap. This notorious scene is among the most nakedly sadistic Gould ever staged. Mrs. PF's demise winds up being rather contrived, but you'll leave the company of this dreadful duo thanking your lucky stars that you weren't invited to the wedding reception.

As threatening and vicious a villain as Pruneface is, he's basically a dry run (dry? prunes? that's a joke, son) for the very similar, and somewhat more fully characterized, Brow of the following year. Pruneface's sabotage, if successful, would have led to the killing of many civilians, but his persona lacks the clever, humanizing touch that was given to The Brow when the latter fell for Gravel Gertie. What makes the Pruneface tale memorable is that it's bookended by Tracy's near-fatal encounter with the hideous Mrs. Pruneface, who craves revenge for her husband's death (actually, she was operating under a false assumption, as PF would make a comeback many years later) and seeks to enforce it using the aforementioned death trap. This notorious scene is among the most nakedly sadistic Gould ever staged. Mrs. PF's demise winds up being rather contrived, but you'll leave the company of this dreadful duo thanking your lucky stars that you weren't invited to the wedding reception.Flattop is, of course, a legendary villain, and Gould handles his introduction, motivations, and characterization in just the right ways. In his intro, Max Allan Collins rightly describes the scene in which Flattop is about to shoot Tracy as one of the best Gould ever did. The narrative does cut off in the middle of the story, but at a logical "pause point" that serves as an ideal hook for the next volume in the series. (This lacuna also points up the fact that Flattop proved to be so hugely popular with the public -- with a world war competing for people's attention, mind you -- that Gould decided to keep him around for longer than he'd originally planned.) Flattop shines all the brighter in comparison to the ghastly Laffy, the cackling, rotund drug kingpin who's laid low just before the imported killer nonchalantly blows into town. Laffy's character design and shtick are both immensely irritating, which I suppose was the point, but the manner of his ultimate demise shouldn't have been wished on Tracy's most feared foe. In his TRACY history, Jay Maeder called Laffy's lengthy decline "a good laugh," but it's more pathetic than anything else.

The real gem of this era is the story of 88 Keyes, the sallow-faced piano virtuoso. I loved this story when I read it in abridged form in THE CELEBRATED CASES OF DICK TRACY, and the complete version is even better. Keyes certainly isn't grotesque in a physical sense, but his character is pitch-black, correctly described by Collins as that of a "charming sociopath." Keyes' crimes transcend the immediately topical -- though the story does acquire a wartime-flavored subplot when the on-the-lam Keyes has to pose as a farm worker filling in for absent personnel -- and are both relatively mundane (focusing on the old standbys of exploitation and loot-pocketing) and extremely believable. In letting an underage farm girl fall for the pianist, Gould comes very close to a line that is seldom crossed even today and was triply taboo in 1943. The story ends with shocking abruptness as the pursuing Tracy basically takes matter into his own hands; while Tracy would be arraigned in nothing flat these days, his action probably made plenty of sense to readers in a nation at war (and would have reminded those with long memories of some of Tracy's rawer exploits in the previous decade). Marrying the slickness of Gould's drawing style of the 40s to the unvarnished realism of Gould's plots of the 30s, this story stands out, even in a collection that boasts nary a weak spot.

No comments:

Post a Comment